TOURE Lassana. (2023). FINANCEMENT DU CAPITAL HUMAIN DANS LES PAYS DE L’UEMOA : ANALYSE EN DONNEES DE PANEL DE L’IMPACT DES SOURCES DE DEPENSES DE L’EDUCATION ET LA SANTE. Revue economie et société, 2(2), 48–62.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7916250

| TOURE Lassana Enseignant chercheur Université de Ségou, Mali |

RESUME

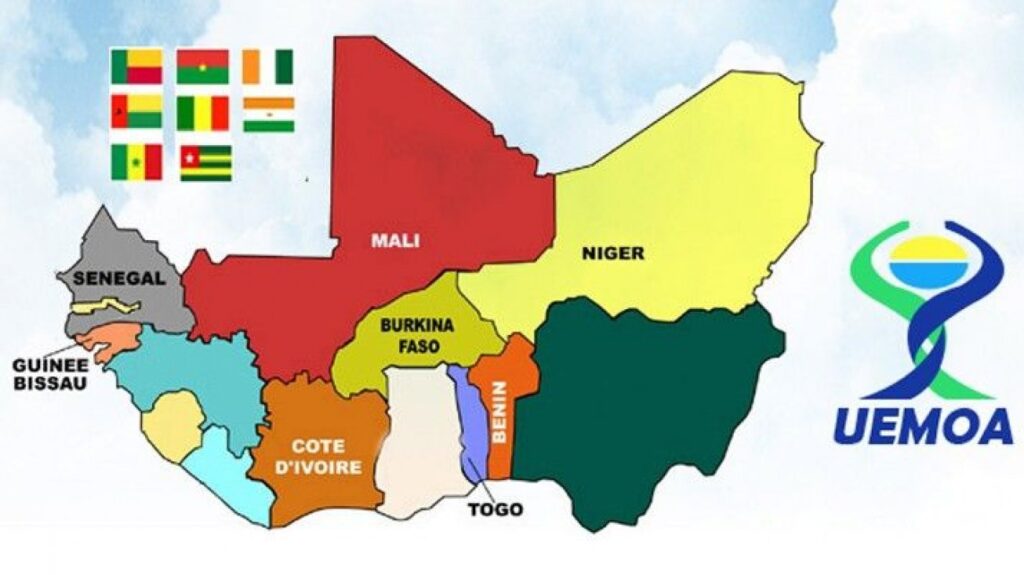

D’importants fonds ont été alloués dans le capital humain, et pourtant les pays en développement ont toujours un niveau de capital humain extrêmement faible. Ce papier a pour objectif de déterminer les sources de dépenses impactant le capital humain dans les pays de l’UEMOA sur la période 2000-2019. Avec un modèle de panel à correction d’erreur prenant en compte la violation des hypothèses classiques (l’autocorrélation et l’hétéroscédasticité des résidus), les résultats ont montré que le PIB par habitant et l’investissement direct étranger (IDE) entrant impactent positivement à long terme l’indice du capital humain au seuil de cinq pour cent. En outre, les dépenses publiques et les transferts de fonds des migrants ont un impact négatif significatif sur le capital humain à long terme. Cependant, l’effet des dépenses publiques à court terme est positif. En adoptant une meilleure réallocation des richesses créées (répartition optimale de la valeur ajoutée, inclusion sociale), prônant la politique de l’attractivité et octroyant davantage dans les dépenses en capital humain (investissements, subventions), les Etats seraient en mesure de rehausser le niveau de capital humain. Une politique monétaire au sein de l’UEMOA permettant de mieux capter les transferts de migrants pourrait favoriser le développement du capital humain.

Mots clés : Capital humain, éducation, investissements, UEMOA, données de panel

FINANCING HUMAN CAPITAL IN WAEMU COUNTRIES: PANEL DATA ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACT OF EDUCATION AND HEALTH EXPENDITURE SOURCES

ABSTRACT

| TOURE Lassana Lecturer and researcher University of Segou, Mali |

Significant funds have been allocated to human capital, yet developing countries still have extremely low levels of human capital. This paper aims to determine the sources of expenditure impacting human capital in WAEMU countries over the period 2000-2019. Using an error-correction panel model that takes into account the violation of classical assumptions (autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity of residuals), the results show that GDP per capita and inward foreign direct investment (FDI) have a positive long-term impact on the human capital index at the five per cent threshold. In addition, public expenditure and migrant remittances have a significant negative impact on human capital in the long run. However, the effect of public spending in the short run is positive. By adopting a better reallocation of created wealth (optimal distribution of value added, social inclusion), advocating attractiveness policies and providing more in human capital expenditure (investments, subsidies), states would be able to raise the level of human capital. A monetary policy within the WAEMU that allows for a better capture of migrant remittances could favour the development of human capital.

Keywords: Human capital, education, investments, WAEMU, panel data

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Arturo, R. (2001). Foreign direct investment as a catalyst of human capital accumulation. submitted in fulfilment of the MALD thesis requirement. http://dl.tufts.edu/catalog/tufts:UA015.012.DO.00007 consulté le 25 septembre 2021.

Azam, M., Khan, S., Zainal, Z. B., Karuppiah, N. & Khan, F. (2015). Investissement direct étranger et capital humain : preuves des pays en développement. Gestion des investissements et innovations financières, 12(3-1), 155-162.

Banque mondiale. (2021). Base de données de la Banque mondiale. https://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicator. consulté le 25 septembre 2021.

BCEAO. (2021). Banque de données économiques et financières de l’UEMOA. https://www.bceao.int/fr/content/la-base-des-donnees-economiques-et-financieres consulté le 25 septembre 2021.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education. University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2) : 9-49. DOI :10.1086/258724

Benos, N. & Zotou, S. (2014). « Education and Economic Growth: A Meta-Regression Analysis », MPRA Paper No. 46143.

Blomstrom, M. & Kokko, A. (2002). FDI and human capital: a research agenda. Working Paper, No. 195, CD/DOC (2002)07 OECD Development Centre.

Weisbrod, B. A. (1962). Education and Investment in Human Capital. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(5) : 106-123, Part 2: Investment in Human Beings, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1829107 consulté le 25 septembre 2021.

Checchi, D., Simone, D.G. & Faini, R. (2007). Skilled migration: FDI and human capital investment. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 2795, P.O. Box 724053072 Bonn Germany.

Denison, E. (1962). The Sources of Economic Growth in the United States and the Alternative Before Us. New York: Committee for Economic Development.

Dia, A. A. (2005). Education, capital humain et dynamique économique : analyse à partir du secteur industriel sénégalais. Université de Bourgogne, Thèse.

Egger, H., Egger, P., Falkinger, J. & Grossmann, V. (2005). International capital market integration, educational choice and economic growth. Cesifo Working Paper, No. 1630.

Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R. & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The Next Generation of the Penn World Table. American Economic Review, 105(10) : 3150-3182. www.ggdc.net/pwt consulté le 25 septembre 2021.

Gittens, D. & Pilgrim, S. (2013). Foreign direct investment and human capital: a dynamic paradox for developing countries. Journal of Finance, Accounting and Management, 4(2) : 26-49.

Gupta, S., Pattillo, A. C. & Wagh, S. (2009). Effect of Remittances on Poverty and Financial Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 37(1) : 104-115.

Heylen, F., Schollaert, A., Everaert, G. & Pozzi, L. (2003). Inflation and human capital formation: theory and panel data evidence. Working Paper, No. 2003/174- D/2003/7012/12, SHERPPA, Ghent University, Belgium.

Iatagan, M. (2015). Consequences of the Investment in Education as Regards Human Capital. Procedia Economics and Finance, (23) : 362-370

Marginson, S. (2017). Limitations of human capital theory. Studies in Higher Education, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1359823.

Mincer, J. (1981). Human capital and economic growth. NBER Working Paper, No. 803.

Ndeffo, L. N. (2010). Foreigndirect investments and human capital development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economics and Applied Informatics, XVI (2) : 37-50.

OCDE. (2021a). Education at a Glance. https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/ consulté le 25 septembre 2021.

OCDE. (2021b). Private spending on education (indicateur).

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/fr/education/education-resources/indicator-group/french_973dcde1-fr consulté le 25 septembre 2021.

Psacharopoulos, G. (1994). Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Development, 22(9) : 1325-1343.

Ruttan, V. W., Yujiro, H. (1988). Consequences of the Demographic Rapid Increasing in the Countries under Development, edited by G. Tapinos, D. Blanchet and D.E. Horlacher, Institut National d’Etudes Demographiques, Division de la Population des Nations Unies, 113-141.

Schultz, T.W. (1963). The economic value of education. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schultz, T.W. (1961). Investment in Human Capital. American Economic Review, 51(1) : 1-17.

Shafuda C. P.P. & De U. K. (2020). Government Expenditure on Human Capital and Growth in Namibia: A Time Series Analysis. Journal of Economic Structures, 9(21), 1-14. Zhuang, H. (2008). Foreign direct investment and human capital accumulation in China. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, (19) : 205-215

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.